building a neural network using transfer learning

If you were to build a basic image classifier, you don’t want to reinvent the wheel. That is to say, there is almost no need to train your neural network from scratch. Instead, you can “transfer learning”, in which you’re going to use the trained network weights. Otherwise, you would have to prepare tens of thousands of training images. In terms of transfer learning, there are two major approaches out there, which are pre-training and fine-tuning. In this project, there is no significant difference between those from the accuracy’s standpoint. A fine-tuning method marked 89.2% of accuracy while pre-trained with 88.5%.

The network I chose is ResNet. I chose this because it’s memory efficient and very accurate in many cases. But other good models[1] such as GoogLenet or Inception etc are also available with the deep learning library.

Of course, there are always many rooms in order to get the better end-results because tweaking a neural network requires many parameters, therefore, pushing the last 1% of the inference accuracy sometimes needs a lot of effort. At this time, putting those tweaking parameters aside, I want to compare rather more basic strategy, which is, building a network from scratch vs pre-training vs fine-tuning.

commands and programs

The script I used for the training is basically based on the official tutorial[2] code by PyTorch. On top of that, I just modified a few parameters as follows.

learning rate: 0.001

epochs: 10

batch size: 4

# usage:

# python transfer_learning.py [data directory] [logfile]

# Modified from the licensed codes below

# License: BSD

# Author: Sasank Chilamkurthy

from __future__ import print_function, division

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.optim as optim

from torch.optim import lr_scheduler

import torchvision

from torchvision import datasets, models, transforms

import time, sys, os, copy

import numpy as np

log = open(sys.argv[2], 'w')

# Data augmentation and normalization for training

# Just normalization for validation

data_transforms = {

'train': transforms.Compose([

transforms.RandomResizedCrop(256, (0.5, 1.0), (1.0, 1.0)),

transforms.CenterCrop(224),

transforms.RandomHorizontalFlip(),

transforms.ToTensor(),

transforms.Normalize([0.485, 0.456, 0.406], [0.229, 0.224, 0.225])

]),

'val': transforms.Compose([

transforms.Resize(256),

transforms.CenterCrop(224),

transforms.ToTensor(),

transforms.Normalize([0.485, 0.456, 0.406], [0.229, 0.224, 0.225])

]),

'test': transforms.Compose([

transforms.Resize(256),

transforms.CenterCrop(224),

transforms.ToTensor(),

transforms.Normalize([0.485, 0.456, 0.406], [0.229, 0.224, 0.225])

]),

}

data_dir = sys.argv[1]

image_datasets = {x: datasets.ImageFolder(os.path.join(data_dir, x),

data_transforms[x])

for x in ['train', 'val', 'test']}

dataloaders = {x: torch.utils.data.DataLoader(image_datasets[x], batch_size=4,

shuffle=True, num_workers=4)

for x in ['train', 'val', 'test']}

dataset_sizes = {x: len(image_datasets[x]) for x in ['train', 'val', 'test']}

class_names = image_datasets['train'].classes

device = torch.device("cuda:0" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu")

def train_model(model, criterion, optimizer, scheduler, num_epochs=25):

since = time.time()

best_model_wts = copy.deepcopy(model.state_dict())

best_acc = 0.0

for epoch in range(num_epochs):

print('Epoch {}/{}'.format(epoch, num_epochs - 1))

print('-' * 10)

log.write('Epoch {}/{}\n'.format(epoch, num_epochs - 1))

log.write('-' * 10)

log.write('\n')

# Each epoch has a training and validation phase

for phase in ['train', 'val', 'test']:

if phase == 'train':

scheduler.step()

model.train() # Set model to training mode

else:

model.eval() # Set model to evaluate mode

running_loss = 0.0

running_corrects = 0

# Iterate over data.

for inputs, labels in dataloaders[phase]:

inputs = inputs.to(device)

labels = labels.to(device)

# zero the parameter gradients

optimizer.zero_grad()

# forward

# track history if only in train

with torch.set_grad_enabled(phase == 'train'):

outputs = model(inputs)

_, preds = torch.max(outputs, 1)

loss = criterion(outputs, labels)

# backward + optimize only if in training phase

if phase == 'train':

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

# statistics

running_loss += loss.item() * inputs.size(0)

running_corrects += torch.sum(preds == labels.data)

epoch_loss = running_loss / dataset_sizes[phase]

epoch_acc = running_corrects.double() / dataset_sizes[phase]

print('{} Loss: {:.4f} Acc: {:.4f}'.format(phase, epoch_loss, epoch_acc))

log.write('{} Loss: {:.4f} Acc: {:.4f}\n'.format(phase, epoch_loss, epoch_acc))

# deep copy the model

if phase == 'val' and epoch_acc > best_acc:

best_acc = epoch_acc

best_model_wts = copy.deepcopy(model.state_dict())

print()

log.write('\n')

time_elapsed = time.time() - since

print('Training complete in {:.0f}m {:.0f}s'.format(time_elapsed // 60, time_elapsed % 60))

print('Best val Acc: {:4f}'.format(best_acc))

log.write('Training complete in {:.0f}m {:.0f}s\n'.format(time_elapsed // 60, time_elapsed % 60))

log.write('Best val Acc: {:4f}\n'.format(best_acc))

# load best model weights

model.load_state_dict(best_model_wts)

return model

model_conv = torchvision.models.resnet18(pretrained=True)

#for param in model_conv.parameters():

# param.requires_grad = False

# Parameters of newly constructed modules have requires_grad=True by default

num_ftrs = model_conv.fc.in_features

model_conv.fc = nn.Linear(num_ftrs, 2)

model_conv = model_conv.to(device)

criterion = nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

optimizer_conv = optim.SGD(model_conv.fc.parameters(), lr=0.001, momentum=0.9)

# Decay LR by a factor of 0.1 every 7 epochs

exp_lr_scheduler = lr_scheduler.StepLR(optimizer_conv, step_size=7, gamma=0.1)

model_conv = train_model(model_conv, criterion, optimizer_conv, exp_lr_scheduler, num_epochs=10)

One thing that I want to note is that the fully-connected layer at the end of the network is project specific. In other words, you should set the right number of nodes according to your classes of the data.

num_ftrs = model_conv.fc.in_features

model_conv.fc = nn.Linear(num_ftrs, 2)

training with GPU

To enjoy the power of the on-demand GPU instances, cloud platforms such as AWS, GCP, or Azure will be the first choice. I chose AWS because there is machine learning OS image in which a lot of handy tools are pre-installed, which is so easy to use. And the hardware that I used is an AWS P2 GPU instance (1 K80 GPU, 4 vCPU, 61 GiB RAM). With the AWS’s deep learning AMI, smooth and quick start is possible.

It takes a few minutes to train the network.

Epoch 0/9

----------

train Loss: 0.5825 Acc: 0.7469

val Loss: 0.3196 Acc: 0.8824

test Loss: 0.3056 Acc: 0.8883

Epoch 1/9

----------

train Loss: 0.5767 Acc: 0.7627

val Loss: 0.4760 Acc: 0.8626

test Loss: 0.4525 Acc: 0.8755

Epoch 2/9

----------

train Loss: 0.5955 Acc: 0.7631

val Loss: 0.3651 Acc: 0.8597

test Loss: 0.3174 Acc: 0.8715

Epoch 3/9

----------

train Loss: 0.5804 Acc: 0.7671

val Loss: 0.3384 Acc: 0.8824

test Loss: 0.2855 Acc: 0.8874

Epoch 4/9

----------

train Loss: 0.5861 Acc: 0.7681

val Loss: 0.3921 Acc: 0.8824

test Loss: 0.3655 Acc: 0.8834

Epoch 5/9

----------

train Loss: 0.6172 Acc: 0.7598

val Loss: 1.0636 Acc: 0.6927

test Loss: 1.0862 Acc: 0.7026

Epoch 6/9

----------

train Loss: 0.6108 Acc: 0.7581

val Loss: 0.6338 Acc: 0.8014

test Loss: 0.6197 Acc: 0.7955

Epoch 7/9

----------

train Loss: 0.4601 Acc: 0.8027

val Loss: 0.3158 Acc: 0.8854

test Loss: 0.2824 Acc: 0.8903

Epoch 8/9

----------

train Loss: 0.4466 Acc: 0.8002

val Loss: 0.3944 Acc: 0.8439

test Loss: 0.3604 Acc: 0.8508

Epoch 9/9

----------

train Loss: 0.4320 Acc: 0.8059

val Loss: 0.3080 Acc: 0.8923

test Loss: 0.2920 Acc: 0.8903

Training complete in 25m 31s

Best val Acc: 0.892292

the achieved accuracy

The best accuracy has been marked by fine-tuning, topping 89.2%. While the one with pre-training followed with 88.5%. On the other hand, the non-pretrained network marked just 70% at best.

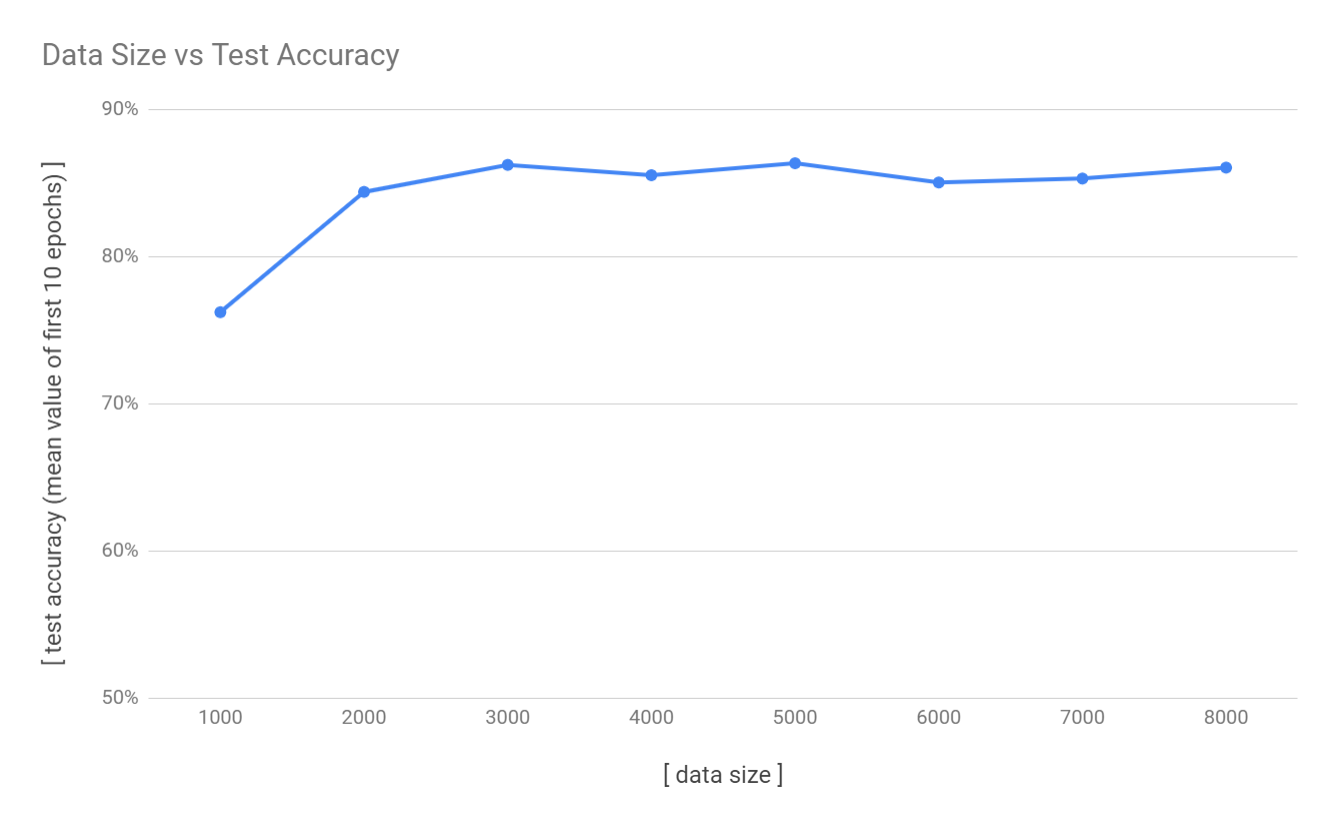

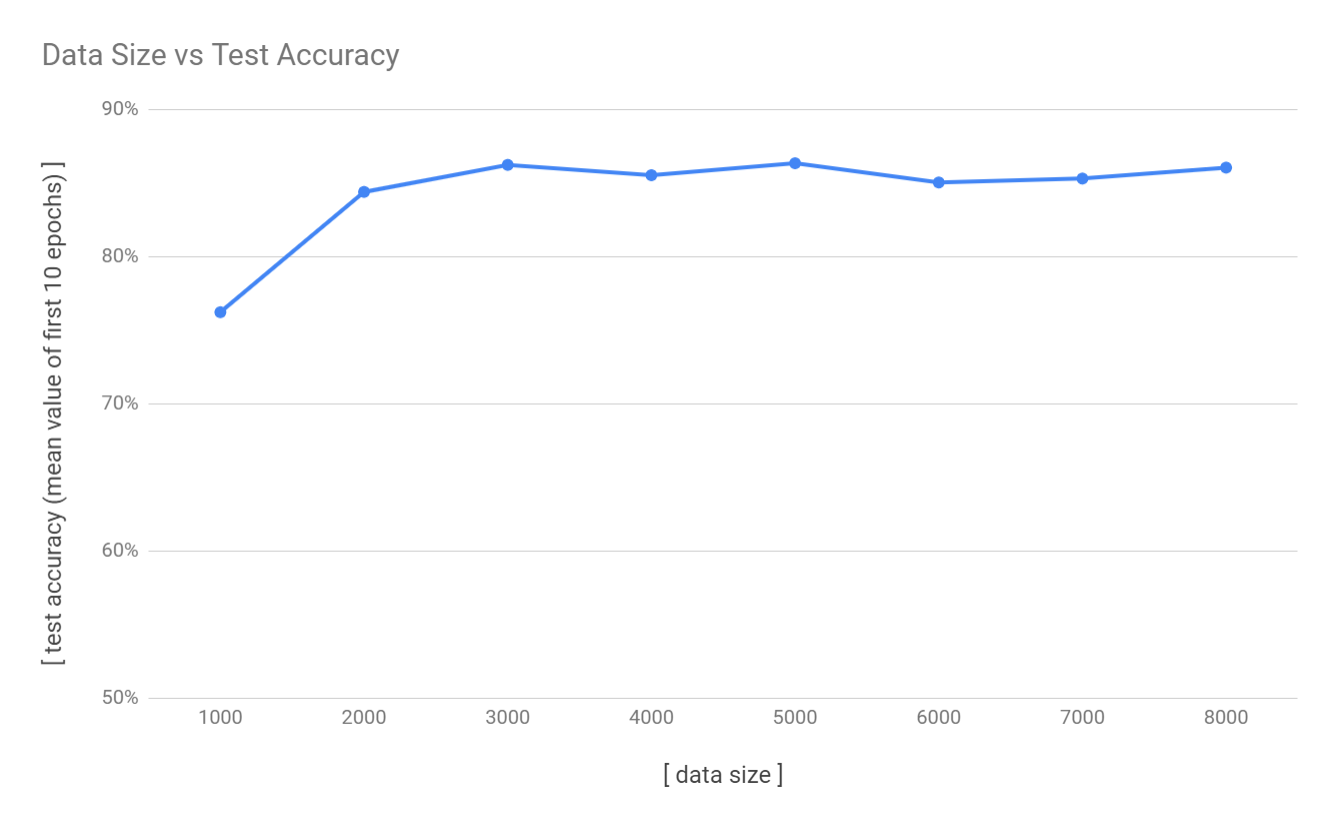

the accuracy and the data size

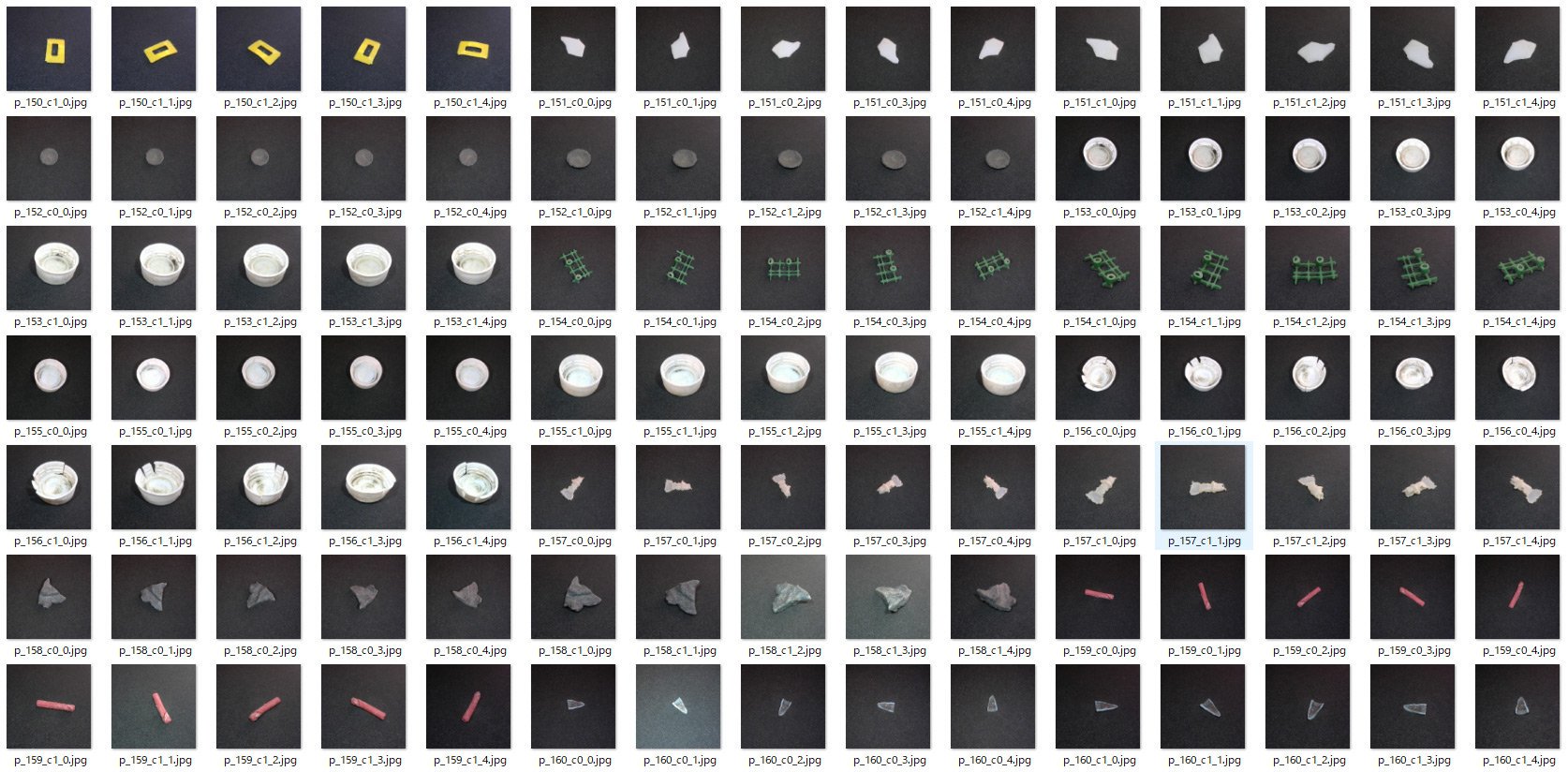

In my opinion, the appropriate amount of training data really depends on the quantity of the latent features of the training data. Hense, it’s most likely impossible to calculate the required size of your training data with one simple formula. In this case, it turned out that I have prepared too much data. More precisely, in this case, most of the features of my training data are redundant. I assume that this is because I shot each plastic samples from various angles and I have inflated the data size by a factor of 10. Regarding this point, shooting a sample from 10 different angles is way too much. Judging from the chart below, I conclude that, in this case, the optimal size of training data is 2000 and that more data don’t add essential features to the network. That means, when I have 1000 physical samples, shooting from 2 angles is very efficient.

conclusion

I built a simple AI that can see if a fragment from the beach debris is whether plastic or not. With that neural network trained with my home-made training dataset, the accuracy marked 89.2%.

The pre-trained ResNet on the deep learning library PyTorch and AWS’s deep learning AMI enabled me to skip all the tasks for the setting up the work environment. This advantage allows me to focus on the training itself.

In terms of my training data, 10,000 image data for 1,000 physical samples turned out to be highly redundant. However, shooting a sample from 2 angles is a good way to enrich the latent features of the training data.

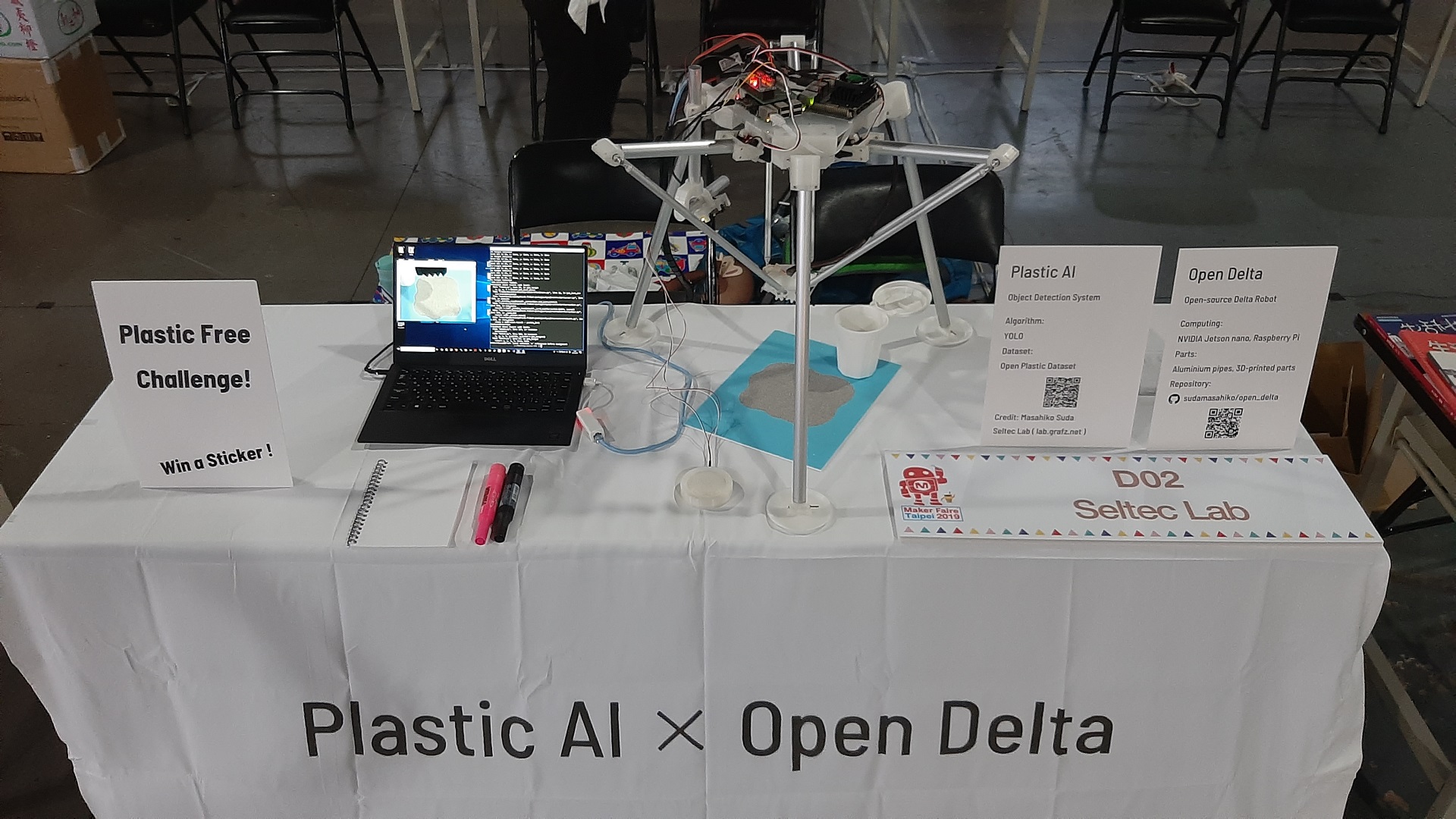

There’s a long way to go through. What I really need for this project is object detection, not a simple image classifier. The project continues.

[1] TORCHVISION.MODELS

https://pytorch.org/docs/stable/torchvision/models.html

[2] TRANSFER LEARNING TUTORIAL

https://pytorch.org/tutorials/beginner/transfer_learning_tutorial.html